this post was submitted on 08 Jan 2026

86 points (96.7% liked)

GenZedong

4999 readers

124 users here now

This is a Dengist community in favor of Bashar al-Assad with no information that can lead to the arrest of Hillary Clinton, our fellow liberal and queen. This community is not ironic. We are Marxists-Leninists.

See this GitHub page for a collection of sources about socialism, imperialism, and other relevant topics.

This community is for posts about Marxism and geopolitics (including shitposts to some extent). Serious posts can be posted here or in /c/GenZhou. Reactionary or ultra-leftist cringe posts belong in /c/shitreactionariessay or /c/shitultrassay respectively.

We have a Matrix homeserver and a Matrix space. See this thread for more information. If you believe the server may be down, check the status on status.elara.ws.

Rules:

- No bigotry, anti-communism, pro-imperialism or ultra-leftism (anti-AES)

- We support indigenous liberation as the primary contradiction in settler colonies like the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Israel

- If you post an archived link (excluding archive.org), include the URL of the original article as well

- Unless it's an obvious shitpost, include relevant sources

- For articles behind paywalls, try to include the text in the post

- Mark all posts containing NSFW images as NSFW (including things like Nazi imagery)

founded 5 years ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

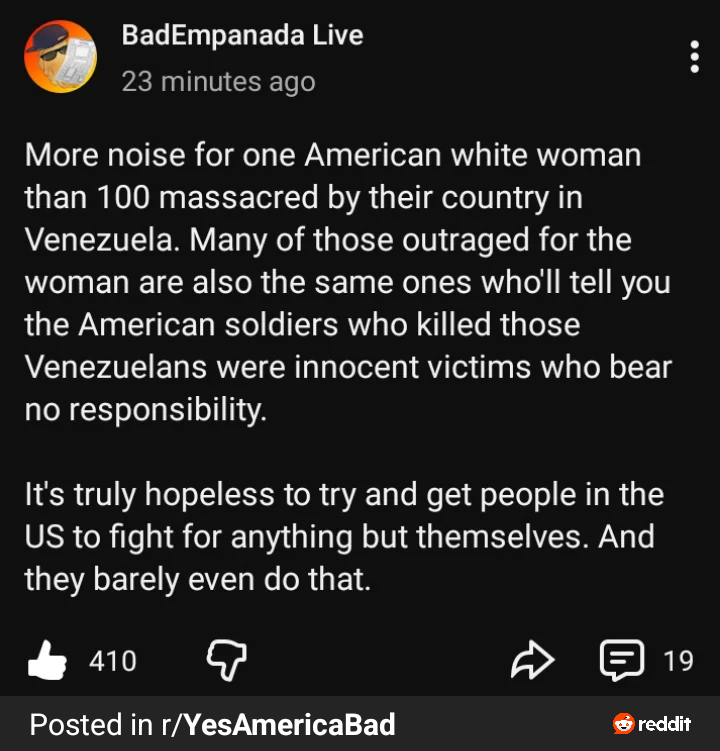

I agree with you on the IRA, and more than that, I see it as a clear example of an anti-imperialist, anti-colonial movement that extracted real material gains from a vastly more powerful state. Whatever one thinks of its limitations or internal contradictions, the IRA and the broader republican movement forced the British state to negotiate, reshaped the political terrain in Ireland, and secured concrete concessions that would have been impossible through moral appeal or symbolic protest alone. It didn’t achieve everything it set out to, but it demonstrated decisively how mass community support, disciplined organization, clear objectives, and a credible capacity for escalation can make an occupying power unable to simply ignore resistance. If I had to point to a broader analytical frame before listing examples, as I did elsewhere in this thread, I’d flag two texts that get at the underlying problem. Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle is useful for understanding how, in advanced capitalist societies, representation, spectacle, and performance replace real action and interaction. Politics becomes something to be seen rather than something that exerts force. Jones Manoel’s essay Western Marxism, the Fetish for Defeat, and Christian Culture is important for explaining why even the Western left internalizes this logic, mistaking visibility, suffering, and moral witness for power, and repeatedly reproducing forms of action that feel meaningful but are materially ineffectual. Historically, politically meaningful protest, even in the West, has looked very different. It has depended on mass organization, clear material demands, and a credible threat of escalation. During the U.S. civil rights movement, disciplined organizations like the NAACP, SCLC, and CORE coordinated sustained campaigns, while armed self-defense formations such as the Deacons for Defense made repression costly and instability plausible. Later, the Black Panther Party took this further by combining political education, mass programs, and armed deterrence, precisely why it was met with assassination, infiltration, and destruction. A third example is the early labor movement. Strikes worked not because workers marched politely, but because organized labor could shut down production, disrupt profits, and escalate to militancy if ignored. The difference between these cases and modern Western “parades” (a term I’ll continue to use because it best captures the structure) is decisive. Effective movements were not oriented toward spectacle, moral signaling, or catharsis. They were oriented toward leverage. They built durable organizations, articulated concrete demands, and created conditions in which ignoring them carried real costs. Contemporary Western “protests”, whether riots that burn out quickly or sanctioned marches that dissipate harmlessly, lack those fundamentals. That’s why they are absorbable. And that’s why, analytically, they function less as protests in the classical sense and more as managed expressions of dissent within a system that no longer fears them, angry parades rather than challenges to power.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on it. I've read Jones Manoel's essay before multiple times, but I'll have to make a note to look into Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle.

The point about the power of negotiation, disruption, etc., I try to think of what signs there are left of this in the US and all I can think of that seems noteworthy is newer union efforts. (Older ones, to my understanding, often suffer from problems of diluted power/influence.) But then I also read stories about one business or another, where a union was being formed and the company shut down entirely the branch it was being formed at in order to stop the unionization.

In general, the modern USian "left" seems broadly mired in a mode of thinking and strategy that goes something like the following: "The constitution gives people certain legal human rights (at least in theory). Rather than challenging the validity of relying on an old document built out of a settler-colonial project that committed genocide and was built through slavery, we start with the belief that the constitution had the right idea but never actualized it. Therefore, to fix problems, we act within the framework of behaving in a way that is legal (as it pertains to theoretical rights provided by the constitution) and challenging what is illegal (as it pertains to theoretical rights provided by the constitution)."

In this way, "civil disobedience" (which often translates to the kind of protest we're talking about) can be viewed as an actualization process of the constitution rather than a challenge to it. What little potentially "illegal" action people are willing to take becomes a validation of the state project and its origins rather than an invalidation of it. I'm not sure this is what the left wants to be doing as strategy, but it may be somewhat of a fear/survival response to the violence of imperial repression and the dismantling of more militant efforts. The general thought process being that by raising awareness, we can become strong enough to transform into the other, more militant form. The problem there, of course, is that transformation does not arise magically out of numbers. Raised awareness and outrage that is not organized and grounded in disciplined theory and practice leads to riot rather than sustained leverage. (Some of this may apply similarly to parts of the EU, but I don't know enough about them to say with confidence one way or another.)